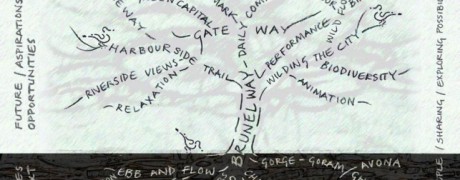

Project tree by landform sculptor Mick Petts, David’s collaborator on Earthed,

Often I find myself working with other writers, trying to find the best process to support their work whilst they’re still in the middle of creating it. There are tried and tested metaphors for describing this that seem really appropriate for Earthed: drawing the map of the land when you haven’t found the edges yet; getting a bird’s-eye view when you can’t help but see the details down with the bugs and beetles, or are digging so far into the subterranean layers of an idea that you’ve lost what needs to be visible on the surface.

This sort of problem became apparent on Day 2 of our process when we had Rachel Aspinwall the Artistic Director of Part Exchange Co, the landform artist Mick Petts and a writer all bringing slightly different levels of understanding to why they were in the same room together. We’d barely begun but Rachel needed a project structure to attract funding and investment; the writer needed to know what the content might be and what written form was therefore required; the landform artist knew they had to make a landform, but couldn’t know where it would be or what it’d be made of.

Admittedly, I was slightly behind in the conversation having been out of the frame in another country for a month, but the importance of defining intentions in these early stages of collaborative work became quickly apparent.

What immediately helped me (simple, but something I’d negated as part of my process until this point) was talking to Mick in more detail over lunch about why, how, for whom and where he does what he does, where he gets his ideas, how he chooses what forms to build, what his process involved – and then to Rachel around what the producing side of the project (about which I’m pretty clueless) actually required to give us the best chance of success.

What I’ve had to resist as a writer in this process is tying down the content too early. I’m not leading on narrative: I’m collaborating on finding out what it could be. Collectively we’ve had to find holding frames for our ideas; big broad brushstrokes of ideas on huge canvases that are as much structural as they are thematic – but they need to hold stories, not be the stories themselves.

So let’s work with the four seasons. Let’s work with the cycle of nature. Let’s turn a brownfield site into a greenfield site. Let’s create a new cycle of mythologies about the land in Bristolacross the generations. The pressures of producing and feasibility on a site-specific piece of this nature means that, as a writer, the beginning of my process has completely inverted and I’m putting structure way before content – something I have warned nearly every writer in the last ten years (and myself) is the road to navel-gazing with form before knowing what it is you really have to say.

For the time being, we are trusting that big canvas of ideas and the big overarching structures – and trusting those little moments of excitement where suddenly something fizzes between us (let’s race up that hill! Look, those mudflats look like dragon scales! Oh my God we’re at the mouth of Bristol’s historic trade route! Wow you’ve just invented a whole world of tree guardians who speak in the language of the wind!) and so on.

It’s leaving me open for longer, and therefore freer to change direction, meander, double-back and let things settle – and I think that can only be a good thing.

Comments are closed