Welcome Back!

Thanks for visiting the Viewing Chamber and welcome to the second digest of The Engine House, Part Exchange Co’s vibrant research and development project exploring site-specific, interdisciplinary theatre with writers at its heart.

The Viewing Chamber is the room in The Engine House where we share with you a broad range of materials coming direct from our artists’ work: on-site discoveries, off-site musings, audio, video, visuals, scribblings, makings, sculptings and scraps… if it forms a crucial part of the creation of the work, you’ll find it here.

The digests are an opportunity for us to look back every three months on the various seed ideas our artists are developing; to consider what we’re learning from their adventures in the world of site-specific and interdisciplinary theatre, and what patterns might be emerging as they get their heads down.

The Story So Far

In my first digest as Artistic Associate we considered what our various collaborative teams were looking forward to, why interdisciplinary work was necessary and why reflecting back on it in a digest might be useful to the artists, and to you as readers. The teams were prepping themselves for action, wondering what the future might hold and how the challenges that lay ahead would shape their journeys.

Two seed ideas were just getting underway. We talked to the artistic team behind Future Tourist – writer Anita Sullivan, creative technologist Tim Kindberg and PECo’s Artistic Director of Rachel Aspinwall – who are developing a performance on a tourist bus that explores the invasive nature of data harvesting and the shifting identities of place and individual in a digital world.

The digest also drew in landform sculptor Mick Petts, Rachel and myself – the artistic team behind Earthed – as we reflected on our early attempts at creating an iconic landform sculpture for Bristol alongside a new land mythology, each created in tandem with local narratives and communities.

And now?

A few months on, these two initial seed ideas have been joined by a third – Sentient City – and another super-duo of artists: writer Tracy Harris and audio-visual artist Tom Lumens who together with Rachel are exploring the possibilities of animating Bristol’s buildings, revealing their stories through text, music, image and sound.

These seed ideas have been full speed ahead in these exploratory stages, creating as many compelling discoveries as they have diverse artistic questions. The perspective from the heart of the Viewing Chamber reveals a hive of industry, as we survey our artists busy at work whilst Rachel curates, probes, protects, holds, inspires confidence and marks out the pathways for each of these seed ideas to evolve into fully-realised productions.

Finding Patterns

In terms of treating these seed ideas collectively and looking for a coherent way of simultaneously presenting them all, I have to admit the first digest was much easier.

Everybody was starting from the same point (the beginning!) and the questions were naturally similar: what’s your individual process? What’s exciting you about the road ahead? What do you think the collaboration might hold that’s going to push you into new areas? This was the unknown journey, uncharted waters, the untrodden path… processes in the abstract, which could be safely pondered at relative distance. In comparison this second digest is trying to connect together what very different sets of artists are now actually doing together in practice, rather than in the abstract.

Firstly it’s worth noting that those artistic differences have been celebrated across the board, as a doorway to original creative process not just original creative output. The teams are investigating how best they can work together, not just what they can make but how they make it – so what’s emerging is a research and development process that is reflexive, identifying what the process could be whilst actually doing it.

Secondly, looking back over the documentation on offer in the Viewing Chamber a few elements appear that share common ground: audience, language, and the desire for human connection with the work. They’re inextricably linked in and of themselves too – as you’ll see below – and spending a little more time on them can hopefully give us a way in to understanding what’s shaping these new artistic relationships.

Language: Context and Interpretation

Future Tourist writer Anita Sullivan suggests the following about site-specific art:

‘…sometimes the spaces you’re in are very much anchored to people’s lives…they have an invested curiosity. Character is environment – character is the audience themselves.’

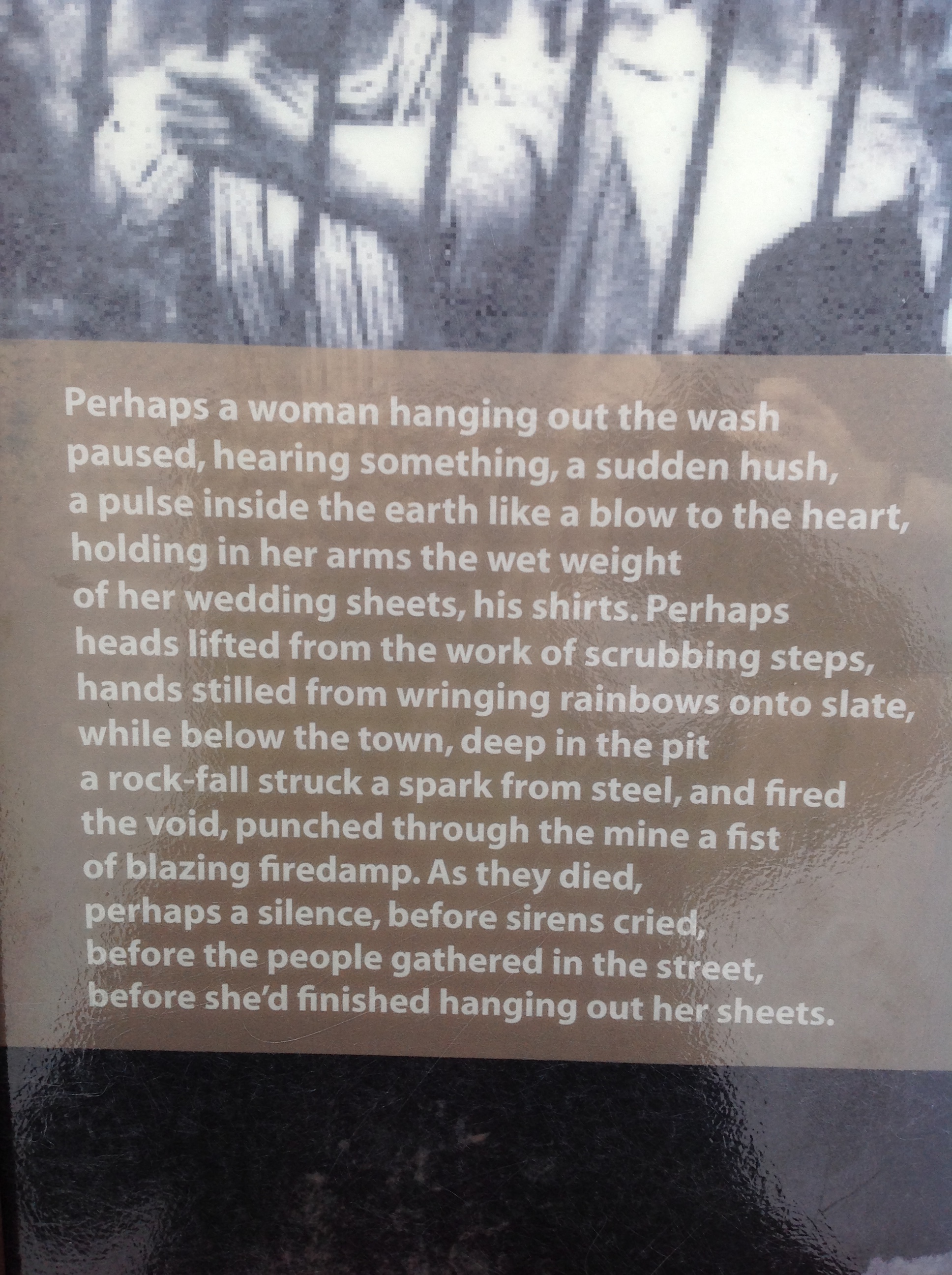

On a hill overlooking the ex-mining town of Six Bells in South Wales, where forty-three miners were killed by a colliery blast in 1960, stands a hauntingly powerful memorial not just to people’s lives, but to the social and economic history that shaped the character of their town.

The Earthed team’s encounter with it – whilst on a search for inspirations for their own landform-writing collaboration – felt like a journey of pilgrimage, even as total strangers.

You have to walk to reach it.

The sculpture is translucent and ghost-like from a distance, light passing through the thousands of tightly-bound steel ribbons that comprise its structure; but as you move closer, it appears both solid and softer. The frame of this huge miner, hands and body opened out towards the town in a paradoxical gesture of strength and supplication is intricately detailed in close-up.

Upon reflection, what hit us was how the emotional journey of meeting the miner was so gently but accurately choreographed. The meaning of the artwork shifts depending on your distance from it, especially for the spectator uninitiated in the town’s history.

From the approaching drive it is anonymous and totemic: a figure looming up, cupped by the sides of the valley but separated from the town’s urban buildings, suggesting a story but without definite context.

At the bottom of the pathway from the unassuming visitor car-park it is part-ghost, letting the light in through its metal skeleton. As the figure appears more solid on the walk up the pathway, so too does its context, as a visitor board offers the facts and figures of what it commemorates. By the time you’re at the foot of its circular plinth engraved with the names of the dead, you’re seeing it not just in its historical but also its physical context as it looks back over the town, defiant and distinctly human.

Only then, as you move away from the statue to take your journey back to the car do you see the visitor board containing Welsh Poet Laureate Gillian Clark’s textual response to the tragedy – positioned almost like an epilogue, visible upon departure rather than arrival at the statue.

It’s hard to express the emotional impact of the whole experience but it’s overwhelmingly theatrical and visceral, felt in your gut.

On our way up the path we were also lucky enough to stumble across a dog-walker who’d lived in the town and was even related to two of the dead. He showed great pride and ownership over the statue.

I’d call that a happy accident but I’m not sure it’s true. We were in the site that related directly to the artwork. The likelihood of having our experience enriched in this way wasn’t accidental. There’s a clear overlap between audience, language and human connection that we need to feed back into our process.

What language is used by those who are anchored to the sites we’re exploring and how does that reveal their deep connection to it? How do they express it – the language of dog-walking? Running? Cycling? Personal memory? Is it the language of gesture and physicality – that a site makes you move differently, breathe differently, requires different exertions? That it calls to you?

For three seed ideas involving writers, there’s also a question of when text is arriving in the performance arena and how it helps generate a sense of deep human connection: through the extremes of solid fact (the number of miners that died and how), expressive reflection (a poet’s imagining of the moment it happened) or chance anecdote (the right person at the right time)?

Much of this boils down to context. No art is made in a vacuum and with site-specific work it’s crucial to access the context of the site and engage those communities connected to it.

In the case of Six Bells the context for initial creation is incredibly clear, but it is shown and introduced so subtly through the style of the work and the journey that is laid out for visitors.

That’s why context is not just about background information: it’s about the work being shapedby the context, responding sympathetically, imaginatively and – where needed – critically towards it. That comes from the artistry of process, the craft of embedding a point of view in the artwork: a clear sense of purpose. It’s what research and development is crucial for identifying.

The gesture, stature, positioning and life-like morphing of density and detail in the miner at Six Bells creates a feeling of human connection because it is imbued with attitude in relation to its context: it goes far beyond a simple act of commemoration and visual impact, and instead tells us the people’s story through their eyes.

Context and Communication: Breaking Down Boundaries

We’ve mentioned above the idea of something being ‘embedded’ in the craft of an artwork – in the case of the miner statue above we’ve identified it as a point of view – but before any artist finds a stimulus for their work, I’d propose that there’s something already embedded in their process that guides their choices.

To grasp at a familiar example: I’d say the dramaturgy of playwriting informs me before I even begin creating – the ‘grammar’ of how to write and structure an effective script for performance is now (hopefully!) in-built. But this grammar isn’t permanently visible to anybody else in the process – not even me – unlike those ‘external’ influences we can identify above, like the physical sites the artists are working in or those sites’ relationships to their visitors.

This part of the digest is therefore going to focus on those elements of the individual artists’ processes that are embedded or ‘internal’ – the learned grammars and structures that quietly inform their choices – to see why they might be useful in the act of collaboration.

At the moment within our seed ideas, these grammars are still operating slightly separately for our artists – one might even say cautiously. For example, both the Sentient City and Earthed teams have operated artistically so far on a call-and-response model of collaboration.

A starting point is established – a building or site – and the artists separate to create a response to it in their own language. Upon returning, they swap responses and then take that other artists’ work away as their stimulus, trying to combine their separate languages but in reference to a common starting point.

Audio-visual artist Tom Lumens responded to the Coroners’ Court in Bristol with the following 60-second piece…

…to which writer Tracy Harris responded with this short text.

Tom references his own piece as:

‘a moving moodboard, layers of images and sounds, closely related to convey an idea or feeling’

but found in Tracy’s response:

‘a really powerful juxtaposition of the dark / gothic images and matter of fact / medical terminology which created something entirely new, but yet still felt resonant with the building. This got me really excited about the possibilities and the potential for meaningful and dramatic outcomes from initial artistic responses.’

From this quick-response exercise to the slow-burn: a similar example of blending languages can be found through the gradual discussion and graft that led to A New Land Mythology, the first consolidation of the writer’s artistic thinking on The Engine House seed idea Earthed.

The team is working with:

- mythology (an abstract context with its own grammar)

- a site (a physical context with its own grammar)

whilst being comprised of…

- a writer-dramaturg (grammar of play structure)

- a landform sculptor (grammar of construction, nature, visual art)

- an artistic director (grammar of performance and participatory development)

The vision driving Earthed is the emergence of a new landform sculpture on a green space in Bristol, designed and built with its communities, and held together by the cycle of changing seasons and a new land-based mythology.

The diagram on page two of A New Land Mythology starts to find parallels between the seasons, their resultant dynamic or action, and how that might translate into the language of story.

The season of winter therefore links:

- Fire and Ice (bonfires and freezing temperatures)

- Decay/Destruction (surface rotting of trees / severe weather)

- Incitement (rock bottom extremes demanding a call to arms from a world and its characters)

In other words the ‘grammars’ of these different elements can start to find ways to combine.

In terms of an overarching structure for the whole piece however, it’s actually the pragmatics of the long-term build of a landform sculpture that has provided an artistic framework.

It begins with the removal of existing land in the space (Destruction – Winter); before the emergence of something new through seeding, planting or building foundations (Spring – Renewal); then is fully realised in a third stage, where plants emerge and foundations firm up to nurture the new shapes in the land (Summer – Birth and Future Seeding); and is then celebrated as it is fully engaged with as a permanent public exhibit (Autumn – Harvest and Abundance).

The deterioration of winter then cycles back in again, evidenced on the surface appearance of the landform (the flowers wilt, the grasses die, the leaves fall and decay).

The idea of a ‘cycle’ suddenly becomes a holding structure, governing not only the shape of the mythology that the writer is creating, but also the building of the landform and how the community participate in it (digging / sowing / reaping), the way it grows and fades and is engaged with through the seasons, and the overarching mythic themes of decay, fertility, renewal and harvest.

Everybody’s different ‘grammars’ for organising the project – pragmatic and artistic – can be held together by one shared central structure or ‘common space’, to borrow Tim Kindberg’s vocabulary.

In his own words:

‘If you bring people from other disciplines in, they will want to appropriate things from you in different ways, use them in ways that you never imagined.’

Breaking the Framework

Combining known languages in this way allows an element of risk but also provides a safety-net: the familiar framework of your own practice (writing, audio-visual art, sculpture).

Collaborations generally do take place within known frameworks, even between audience and the work. We know we’re at a performance. We know that sculpture is non-verbal, poetry isn’t. We know that the language of music on the page looks different to the language of a script, and we know that we need to keep the twin trucks of understanding other artists’ practice and leaving space to surprise one another on track.

So what happens when you go beyond this and completely remove the safety-net? What does that even look like?

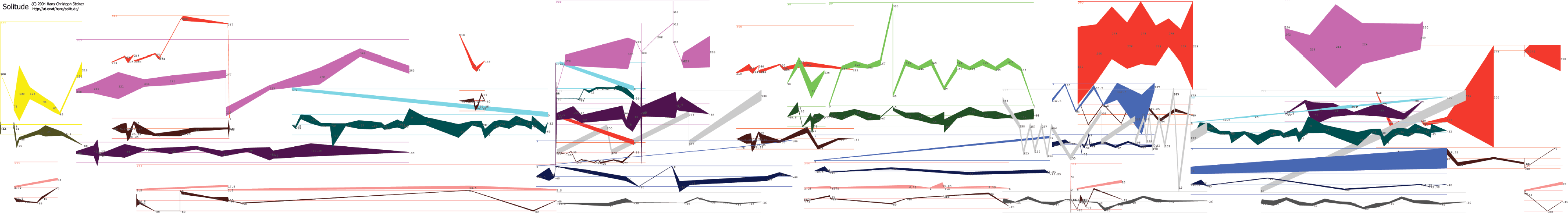

Maybe it looks like the move from this:

To this:

These are both scores for the performance of music.

In terms of clear communication with the audience or artist, the bottom one – graphic notation – can’t get much further from the image of a giant coal-miner statue commemorating a coal-mining tragedy in a Welsh coal-mining town.

They’ve arrived via Tom Lumens, who has brought up graphic notation as part of the Sentient City collaboration.

Put simply on his blog, graphic notation is:

‘The representation of music through the use of visual symbols outside the realm of traditional music notation.’

Further delving in response to Tom’s post led me to the maverick British composer Cornelius Cardew (1936 – 1981) who is responsible for the creation of Treatise – the ‘Mount Everest’ of graphic scores and the composition of which comprises 193 pages of numbers, shapes and symbols whose interpretation is left up to the performer.

If you’re still feeling a bit lost by all this, you can take a look at a fantastically clear, short animated illustration of how one might go about using Treatise creatively – a rough combination of applying existing knowledge of musical notation to unpick the score, but also throwing in tools with their roots in philosophy, visual art and understanding of narrative.

What happens here is a recognised form for communicating the structure, form and delivery of live performance – a musical score – being completely disrupted.

However this potentially becomes a great leveller for two artists from different disciplines. Rather than them setting out separately with a common abstract starting point like a building (i.e. the Coroners’ Court) and then responding to one another’s interpretations of what its structure and dynamic might be, they simply start with a common stimulus that is unfamiliar to both.

Imagine the one pictured above (Hans-Christoph Steiner’s score for Solitude) being used simultaneously by a writer and a musician. Suddenly neither discipline is dominant because both are following the same set of instructions; or both can discover together a set of shared rules for deciphering its information.

The musician is required to think about how colour, shape, angle, repetition and patterning might suggest qualities such as instrumentation, pitch, tempo and volume. The writer is deciphering the same information into arrangements of text, voice, character or action. Perhaps they can do both. And if they’re tuning into one another’s responses, in theory what starts to arrive is a more holistic interdisciplinary performance language from the ground up, rather than one that has to build in layers, to-and-fro, via separate activities.

Two artistic languages are used to unpick and define a third – the collaboration is necessarily finding a new, shared language and structural understanding that works for a specific purpose at a specific time and is responding to a specific shared starting-point. That could be an existing score like the one above, or it could be a building that they then interpret together into a graphic score, which contains neither musical notation or a writer’s text. See Tool Kit #2 for a practical approach to bringing this into collaboration between artists in the r&d space.

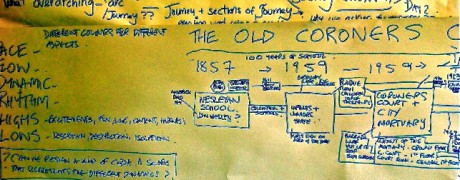

Rachel Aspinwall’s rough notes, halfway through the process of exchanging material in the Sentient City process starts to echo some of these ideas:

…[we need to] explore narrative approaches – including non-linear models, random, fragmented, structured, what works for the piece artistically, practically, pragmatically – to explore this we need to be able to break up any narrative into components that exist within any given folder, so we can explore how it works when we play it in logical progression, and by playing it randomly…

The ‘folders’ are a direct reference to how Tom Lumens stockpiles sound and visual material in a structural framework on his computer, offering material for improvisation in live performance.

If artists can have a shared understanding of a structure with named ‘folders’ along the way, their material too can be blended, twisted and riffed upon whilst containing common – not necessarily directly connected – content.

Tom offers his perfect example of how this might look by referencing the Light Surgeons’ piece Super Everything:

‘…aesthetically it’s this kind of ‘Audio / Visual Tapestry’ that I have in my head when we discuss the mashing of sourced archival content and created artistic reactions to buildings. Weaving elements in and out, using fragments to create a constantly moving collage, putting forward many different elements, texts and ideas, give or create a mood or atmosphere and relay a general feel… I think this type of live cinema shares similarities with much abstract art, in that it gives you motives, snippets and elements and you create your own narratives or meaning from it…’

Which is great for the artists if they understand it all, but what about the audience? What do they make of being confronted with this new performance language?

Audiences: ‘Unreasonable Expectations’

Across all three of the seed ideas, two clear desires have emerged regarding audiences and where they might sit in relation to this new work.

One is the need to push boundaries – to push forms, introduce new theatrical languages and honour the fact that audiences read and experience information in different ways – and the other is the simple desire to create a meaningful human connection between spectator and spectacle.

Creative technologist Tim Kindberg has been working with writer Anita Sullivan on Future Tourist. Upon being asked about his expectations of the collaboration, we got onto discussing expectation through the lens of both audience and artist:

‘…if you have the same kind of people doing the same kind of thing all the time, they have reasonable expectations – but if somebody doesn’t really know what they’re supposed to do they have an unreasonable expectation: and I don’t mean that in a pejorative way, I mean that nothing much ever came of a reasonable expectation.’

I love this comment from Tim not just for its honesty, but for its ability to question the security we might feel in knowledge as artists.

Knowledge is something we’ve underpinned at The Engine House in terms of bringing artists together; we want to understand as much as possible about how somebody else works, what they do and how they think as we begin to co-create. Plus it’s interesting – our artists are working with us not just because they’re talented, but because they want to engage with how other people make their work.

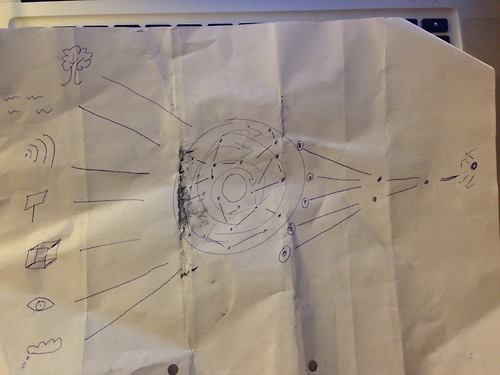

Tim’s comment therefore sits in slight opposition to our recommended Tool Kit #1 for collaborating artists – employed when Sentient City artists Tom Lumens and Tracy Harris first met – where we encourage artists to think through, present and discuss their ‘first draft’ process to one another in a bid to foster a deeper understanding of how somebody else structures their creative thinking.

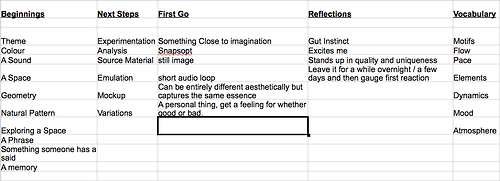

Here’s a diagrammatic and tabled example of how Tom illustrates his:

Sharing this sort of information doesn’t mean we can’t still surprise one another as artists, but it does mean before we shoot out of the starting blocks we have some kind of handle on what the other person might be thinking and doing.

On the other hand of course, you can’t predict it – and if you could, it would be terribly boring – and this is the questioning at the heart of Tim’s comment (and eminently re-usable phrase: unreasonable expectation) that I feel nails a great truth of interdisciplinary work: sacrifice some security to make way for accident, surprise and alchemy – that’s probably where the richest artistic outcomes lie.

But didn’t we start this section talking about audiences? What’s this got to do with them?

Consider the following from Anita Sullivan, Tim’s other half in this collaboration:

‘People absorb information in different ways. Some people are very visual, some people are very audio-based, some people like to be given very little and join up the sum, some people like it presented on a plate, some people like the opportunity to be able to reflect back: so a multidisciplinary approach also gives a multi-audience approach.’

We can’t predict how audiences will read a performance any more than we can predict what our collaborating artists might come up with.

We can try and steer them towards a particular reading by setting parameters or rules through the structure, tone or language of the work itself – or the site it is occupying of course – but as Anita mentions, the languages an audience uses for deciphering a performance are as multiple as the languages we have for communicating performance itself. When you have two different artistic processes mashed together as well, the possibilities seem infinite.

How can we therefore trust that the work is speaking clearly to an audience? More from Anita:

‘It’s two-pronged – it’s what we want to say but also about what expectations the audience might have. It’s thinking about where you want to use those, where you want to support those, where you might want to subvert those or challenge those.’

Expectation – unreasonable or not – is something we can begin to anticipate in both our audiences and our collaborating artists, seeking to recognise the paradigms of theatrical experience or storytelling that they might be anticipating, and then manipulating them as we see fit. It’s a dance of sorts – a ballet of the predictable and chaotic, offering the security of the known alongside the thrill and challenge of the unknown.

Audio-visual artist on Sentient City Tom Lumens names dynamics, motifs, flow and pace as the tools to help structure his compositions; the writer Tracy Harris on the same project names obstacle, drama, and a progression of elements leading to a sense of change as key for her; but in both, there is an implication of an audience’s presence to witness, experience and make sense of the journey those dynamics are creating.

Note to self: the audience is always with us. They define our process. And with inter-disciplinary work, as Anita suggests, our audiences are also invited into a new collaboration:

‘You can bring in a new audience to [interdisciplinary] performance: people who maybe aren’t comfortable in a theatre performance, but wouldn’t think twice about buying a ticket for a gig. It’s a good way to introduce audiences to things that are outside their preconceived comfort zone.’

So perhaps with inter-disciplinary work it’s as useful to talk about the ‘typical’ audiences to our different styles of work as it is our own process – it’s always shaped for them at the end of the day, but why in that way in particular?

Maybe it’s good to acknowledge them more directly. When they encounter the work in production, we’ll want them to be in that same space the artists are now – learning new languages, recognising similarities and willing to be surprised.

In describing models of interdisciplinary work Tim Kindberg used film production as an example where…

‘…everybody works in a common set of spaces… a lot of projects where there aren’t common spaces for people to work in, or common things for people to make together, [are] only kind of multidisciplinary… for me it doesn’t feel real otherwise.’

The ‘common multidisciplinary space’ might sound like a contradiction in terms – but perhaps for both artists and audiences, it’s a fruitful space to target.

Summing Up

The interdisciplinary world feels like a bit of a dichotomy at times.

We want the collisions and the unity.

We want the understanding and the bewilderment.

We want the chaos and the order.

We want to have reasonable and unreasonable expectations, and we want to have the space to risk failing as well as the space to succeed. I’m reminded of Anita Sullivan’s comment in her pre-process interview that ‘no aspect is straightforward and easy’ when it comes to these collaborations.

If anything has characterised the work to date it’s bravery and boldness: courage to open up one’s process to others; courage to collaborate with one another’s very early stage work and lay both yourself and them open to creative criticism; courage to conceptualise and distil and make big structural choices before many other aspects of the project have been shored up; courage to trust that altruism, alchemy and the audience – in all its manifestations – each earn their place in the room.

This digest can only end mid-process, as do these seed ideas, waiting to complete their developmental journeys and come to fruition in the future. We’ve identified commonalities and patterns, and even found some potential methodologies for more effective artistic collaboration: but the proof as ever is in the pudding – so we have to wait and see what our teams serve up next time, and how they’ve digested their own learning into the building blocks for the next stages.